Attached please find the monthly report, in which we share our views on conditions in the financial markets.

The Difference Between Managing And Avoiding Risk

In the June monthly report, we cited a memo from Howard Marks. As co-founder of Oaktree Capital, Marks is a renowned investor in private markets, with a particularly excellent track record in distressed debt. Oaktree is known in the Netherlands, among other things, as the 2021 buyer of the High Tech Campus in Eindhoven.

Excellent returns in the private debt market prompted investment holding company Brookfield to acquire Oaktree in 2019. Marks serves as a commissioner at Brookfield and continues to lead Oaktree Capital.

Marks, however, amassed followers not only because of his good returns, but mainly because of his sharp and witty analyses, which he publishes in memos from time to time. Legendary investor Warren Buffett of investment holding company Berkshire Hathaway is a big fan, and has even said he will drop everything from his hands to read Marks’ new memo when it appears in his mailbox. This week Marks published a new memo titled “Fewer Losers, or More Winners?” A few passages we would like to share with you.

Marks argues in his memo that you can get better returns by having fewer losers or more winners than the leading stock market indices. “If we avoid the losers, the winners will take care of themselves,” reads Oaktree. Marks quotes a similar quote from author Jesse Livermore: “Winners take care of themselves; losers never do.”

Marks: “When you’re aiming for returns well above bond yields, it’s not enough to avoid losers; you have to find winners from time to time. We have several strategies at Oaktree where this is the case. So why do we still use the above phrase as our motto, and why is risk management still the first principle of our investment philosophy? The answer is that we want the concept of risk management to always be at the forefront of our investment professionals’ minds.” We also subscribe to this principle at Tresor Capital.

Difference between risk management and risk avoidance

Marks stresses that understanding the distinction between risk management and risk avoidance is essential for investors: “Risk avoidance basically consists of doing nothing whose outcome is uncertain and could be negative. And yet investing essentially consists of bearing uncertainty in pursuit of attractive returns. For this reason, risk aversion generally equals return avoidance .

You can avoid risk by buying government bonds or putting your money in a savings account, but there is a reason why the returns on these are generally the lowest available in the investment world. Why should you receive a high fee if you waive your money for a while, when you are sure to get it back? Risk management, on the other hand, consists of refusing to take risks that (a) exceed the risk you can live with and/or (b) for which you would not be properly rewarded if you bear those risks.”

Around 1980, a reporter posed a provocative question to Marks: “How can you buy high yield bondswhen you know that some of their issuers will go bankrupt?” Marks answered with what he calls as “the essence of intelligent risk-bearing,” “How can life insurance companies insure people’s lives when they know they will all die?”

Marks explains: “The point is simple: these functions can both be performed in an intelligent, risk-controlled manner. For that to be the case, the risk:

- be a risk of which you are aware,

- be a risk that you can analyze,

- be a risk that you can diversify, and

- a risk for which you are well compensated to take it.

Such risks need not be avoided. If you have good judgment, such risks can be carried wisely and profitably.”

Building a Good Track Record

Marks’ sober analysis shows that it is impossible to achieve exceptional returns without having losers in your portfolio. Marks: “Since (a) all but the most prudent investments carry risk, and (b) the presence of risk means that outcomes will be unpredictable and inconsistent, very few (if any) investors are able to have only good years or build portfolios that contain only winners. The question is not whether you will have losers, but rather how many and how bad relative to your winners.

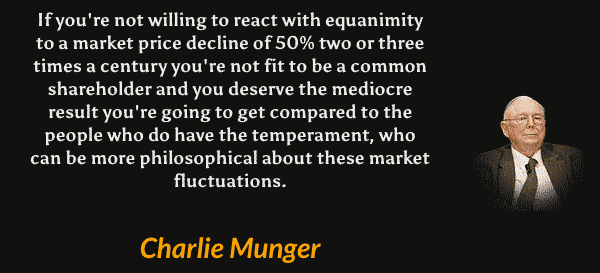

Warren Buffett – perhaps the investor with the best long-term record (and certainly the longest long-term record) – is widely said to have had only 12 big winners in his career. His partner Charlie Munger told me that the vast majority of his own wealth came from just four winners.

I believe the ingredients for Warren and Charlie’s great performance are simple: (a) many investments in which they did quite well, (b) a relatively small number of big winners in which they invested heavily and held for decades, and (c) relatively few big losers. No one should expect – or expect their asset managers to expect – that there are only big winners and no losers.

Indeed, it is not a useful goal to want no losers. The only sure way to achieve that is to take no risk at all. But as I said before, avoiding risk is likely to result in avoiding returns. There is such a thing as taking too little risk. Most people understand this intellectually, but human nature makes it difficult for many to accept the idea that the willingness to live with some losses is an essential ingredient for investment success.”

Charlie Munger shared his unvarnished opinion in 2009 after the sharp share price declines in the credit crisis

The role of risk-taking

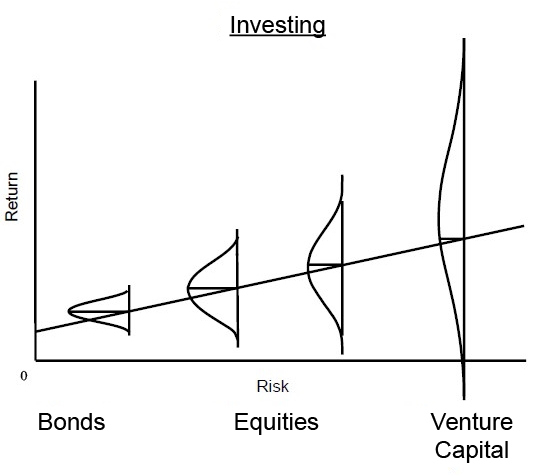

Marks says he was taught during his education 55 years ago that the relationship between risk and return is linear. Marks: “But the more I thought about it, the more unhappy I was with the way the linear presentation of that supposed relationship tells investors that they can count on higher returns as a result of taking more risk. After all, if that were really the case, risky investments would not be riskier.

Rather than implying that taking on more risk guarantees higher returns, my way of looking at the relationship suggests that as you take on more risk, (a) the expected return increases; (b) the range of possible outcomes widens; and (c) the potentially bad outcomes get worse.

In other words, riskier investments introduce the potential for higher returns, but also the possibility of other, less desirable outcomes. Therefore, they are described as riskier. As the chart below shows, a risky approach introduces the potential for huge returns as well as the possibility of loss.”

Marks wonders what is the best place to be on this spectrum. Where do you find the best risk/return ratios? Marks: “The short answer is that according to investment theory – and specifically the Efficient Market Hypothesis – there is no better (or worse) place. The EMH says that markets price stocks such that (a) their price equals their intrinsic value and (b) bearing additional risk is fairly rewarded. Thus, bargains and overpricing cannot exist. This is why, according to the theory, “you can’t beat the market.”

Marks quotes a quote from Albert Einstein: “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is.” If markets are efficient and stocks are always priced correctly, active investing can have no value. And yet I am convinced that there are times when markets are overpriced and times when they are underpriced. There are also times when certain markets or sectors are overpriced or underpriced compared to others. In these cases, some stocks may be priced too high or too low, and so some positions on the risk curve may offer better bargains than others.”

The difference between theory and practice was evident during the credit crisis. Marks: “Theory assumes that investors are rational and objective, but psychological excesses violate that assumption. Take, for example, the investment climate during the 2008-2009 financial crisis.”

Conclusion

The fact that investors are by no means always rational and objective, and thus that the efficient market hypothesis does not hold up in practice, provides an opportunity to take advantage of price differences between stock price and net asset value. In both the family holdings and mutual funds in our portfolio, we see large differences between price and underlying value.

At the end of 2021, the average undervaluation of the family holding portfolio was less than 20%, currently it is 31%. In many ways, a very large undervaluation. Moreover, several companies in the holding and fund portfolios also show a solid increase in undervaluation relative to intrinsic value, so it is safe to speak of a double discount.

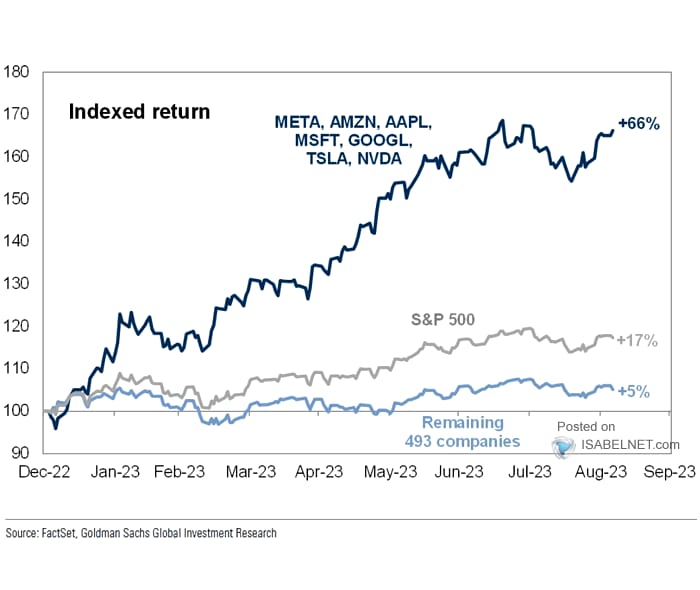

Thus, the risk-return ratio may be considered very attractive. In 2023, however, the average investor seems to only have an eye on stocks of technology companies, largely driven by the enthusiasm surrounding artificial intelligence (AI). Excluding major tech companies, the stock market is only slightly in the plus this year, as shown in the chart above.

Our position is not that these are not good companies, quite the contrary. But the enthusiasm seems to have gone a bit too far, making the risk-return ratio of these technology companies not particularly attractive. The recent share price plunge of Adyen, which fell more than 50% in price after the mid-August release of its half-year results, shows the potential consequences of failing to meet investors’ sky-high expectations.

In their optimism, investors are ignoring other great companies. However, the companies in our portfolio that have not (yet) participated in the recovery manage to do nice deals and grow their intrinsic value. Fundamentally, they are doing well and balance sheets are strong, important characteristics that we watch for from a risk management standpoint.

Moreover, the return on invested capital is excellent, and over time this is the most important indicator of equity returns. After the solid stock market decline in 2022 and the uneven recovery in 2023, investor confidence will be tested, but we are convinced that in the end, the stockholder wins.

If you have any questions or comments about this e-mail or other matters, please kindly contact us using the details below.

Sincerely,

Michael Gielkens, MBA

Partner