Attached please find the monthly report, in which we share our views on conditions in the financial markets. We try to go in-depth, raise important topics for investors, or take a closer look at recent events.

Long-term Focus Versus Everyday Headlines

Last month our mouths dropped open in amazement. After being active in the financial world for a while you are used to something, but with the above article promptly on the front page of the leading financial newspaper in the Netherlands, it is waiting for questions from clients. With surprisingly nuanced content, to which this headline does not do justice, FD journalist Marcel de Boer wrote last month about the rally in equities. After all, since October 2023, the stock market has been on the rise quite a bit.

Analysts from ABN AMRO, Rabobank, ING and Schroders all present cogent arguments as to why new record highs are nothing special, or at least no reason to get out of stocks. But “isn’t every serious crash in equity markets preceded by an all-time high?” wonders De Boer.

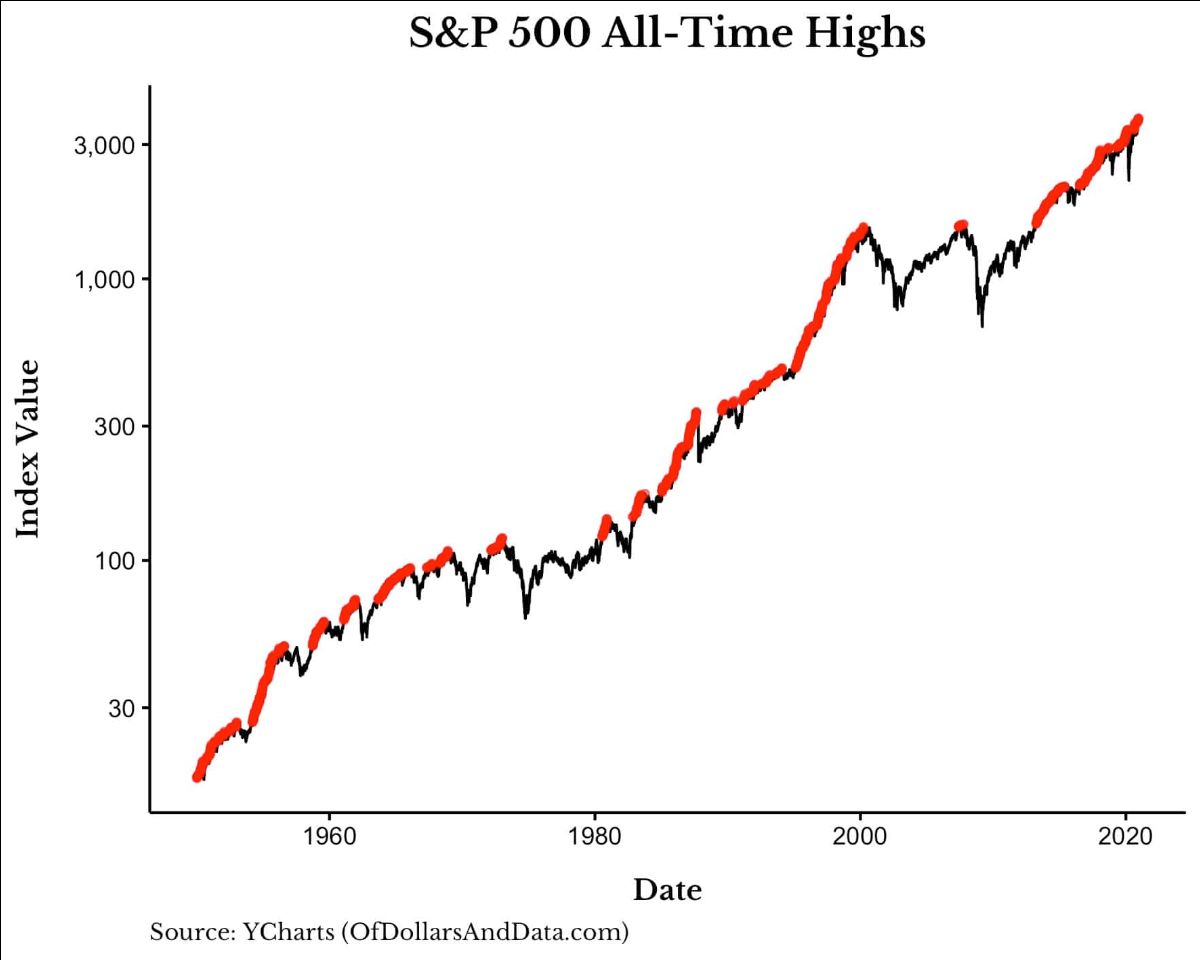

That in itself is a fallacy, and for that we really only need to refer to the stock market chart below, which shows all the historical record highs of the U.S. S&P 500. The broad stock market is at record levels more often than not. Just imagine how many returns you would have missed if you had gotten out at every record low!

To back up his nasty hunch, De Boer dusts off a variable: the CAPE ratio. To give it a sense of authority, it is cited that this ratio was developed by Nobel laureate Robert Shiller. Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel has shown in several research papers that this ratio has clearly lost relevance. Whether one is an advocate or opponent of the ratio, one fact is undeniable: the CAPE ratio is an extremely lousy gauge in terms of stock market timing.

But with nuance, you don’t sell circulation and you don’t get clicks. The result is a frightening headline pointing to a “real risk of a crash.” Perhaps we are sometimes a bit too critical of the financial media, but it would do them good if they were aware of their exemplary role as a source of information and if content prevailed over ad revenue.

USD 1 growth rate from 1802 to 2022, adjusted for inflation. Source: Stocks for the Long Run, Jeremy Siegel.

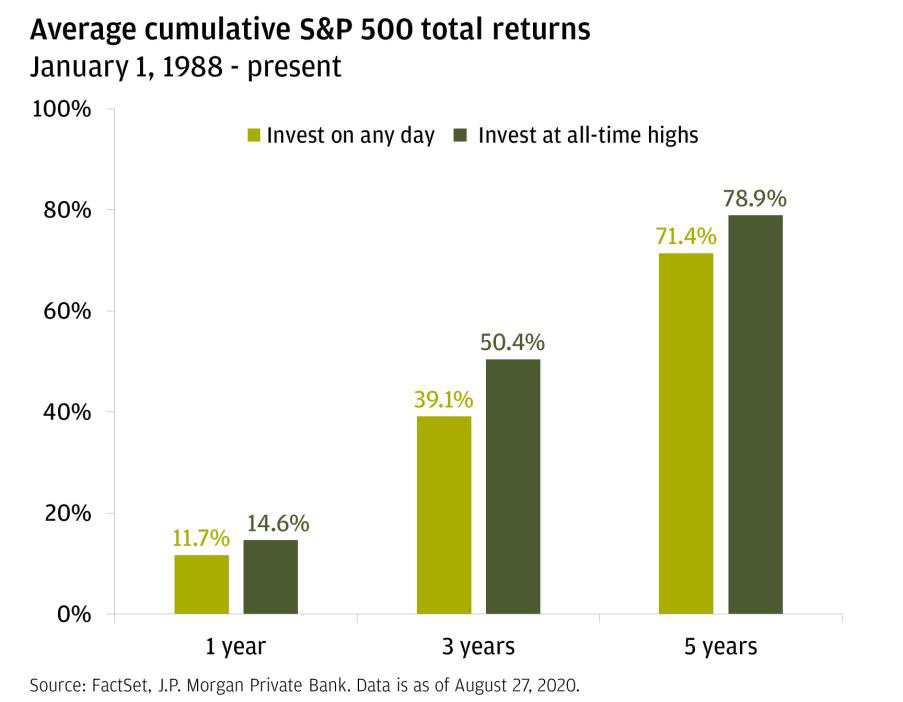

In fact, there is a lot of academic research that shows that record levels in the stock market are not in themselves a reason to panic. We like to let the facts speak for themselves, and we get them from a study by JP Morgan. If you had invested in the S&P 500 index on any given day since 1988, you would have earned a 12% return within a year. If you had invested at a record low, you would have made an average return of 15%.

Corrections will always occur; that’s part of investing. The trick is not to let the headlines scare you away from the stock market. We cite once again the legendary investor Peter Lynch, who averaged a 29% annual return in 13 years as fund manager of the Magellan fund:

Hold on to great companies

At Tresor Capital, we take an active approach. In this sense, we are fairly agnostic to the perceived high valuations of the stock market; we have a selection of quality companies that are grosso modo attractively valued in our portfolio, which offer good diversification both collectively and individually (within holdings, for example). We wrote the following last month:

-

- “Our preference has been and continues to be for relationships that have a horizon of more than five years, and are able to see through price fluctuations, to bring in a well-diversified equity portfolio of high-quality companies, with good and reliable managers and an entrepreneur or family as an anchor shareholder, a high return on invested capital and sufficient opportunities to reinvest profits at that high return. In the long run, this will produce the best results.

-

- It is up to us as managers of our relationships’ assets to navigate between the headlines, keep our eyes on the long term and not panic in the interim.”

In his annual letter to shareholders, Buffett also addressed such issues. It is still sometimes argued that because of Berkshire’s large cash position, Buffett does not have a positive view of the stock market. One could not be further from the truth, Buffett clearly writes:

-

-

- “I expect the return on our equity portfolio to be a very important part of Berkshire’s value growth in the coming decades. Why else would we invest huge amounts of your money in marketable stocks, just as I have done with my own money throughout my investment life? I cannot remember a period since March 11, 1942 – the date of my first stock purchase – when I had not invested most of my wealth in stocks, in U.S. stocks.

America has been a great country for investors. All investors had to do was sit still and listen to no one. “

-

Buffett explains in simple terms what Berkshire Hathaway actually does as a company:

-

-

- “Our goal at Berkshire is simple: we want to own companies with good economic conditions that are fundamentally strong and sustainable. Within capitalism, some companies will prosper for a very long time, while others will turn out to be sinkholes. It’s harder than you might think to predict who the winners and losers will be. And those who tell you they know the answer are usually cheating.

-

-

-

- At Berkshire, we especially prefer the rare companies that can invest additional capital at high returns in the future. Owning just one of these companies – and simply holding them – can yield almost immeasurable wealth. We also hope these favored companies are run by capable and reliable managers.”

-

We fully endorse that one cannot know which companies will be winners or losers. But we are fortunate to have many companies in our portfolio that meet the characteristics in the second paragraph. We rate these companies as having a good chance of delivering a nice risk-adjusted return over the longer term.

Buffett provides an illustration of the investment process at Berkshire using two companies in its equity portfolio:

-

-

-

- “Last year I mentioned two of Berkshire’s long-term minority holdings – Coca-Cola and American Express (AMEX). These are not huge commitments like our Apple investment. Each only accounts for 4-5% of Berkshire’s equity. But they are meaningful assets, and they also illustrate our thought processes.

-

- American Express began operations in 1850 and Coca-Cola was launched in a drugstore in Atlanta in 1886. They were both enormously successful in their operations, which were sometimes adjusted as circumstances demanded. And, crucially, their products “traveled. Both Coca-Cola and AMEX have become globally recognizable names, as have their core products, and the consumption of liquids and the need for unquestioned financial confidence are timeless essentials of our world.

-

- We did not buy or sell a share of AMEX or Coca-Cola in 2023, prolonging our own hibernation, which has now lasted more than 20 years. Both companies rewarded our inaction again last year by increasing their profits and dividends. In fact, our share of AMEX profits in 2023 significantly exceeded the USD 1.3 billion cost of our purchase of the shares long ago.

-

- Both AMEX and Coca-Cola will almost certainly increase their dividends in 2024 – about 16% in the case of AMEX – and we will certainly keep our holdings unaffected throughout the year. Could I create a better global company than these two currently have? No way.

-

- Although Berkshire did not buy shares of either company in 2023, your indirect ownership of both Coke and AMEX increased slightly last year because of the share repurchases we did at Berkshire. Such buybacks increase your holding in each stock Berkshire owns.

The lesson of Coca-Cola and AMEX? If you find a truly great company, stay loyal to it. Patience pays off, and one great company can make up for the many mediocre decisions that are inevitable. “

-

-

Case Study from Tresor Portfolio: Constellation Software

The observant reader of our newsletters, will not be surprised that we have included Berkshire Hathaway as one of the core positions in our equity portfolio. We endorse the lessons Buffett points out above. Another core position is the company Constellation Software. For more information on its business model, please refer to the many weekly newsletters in which we discuss it in detail. The March 15, 2024 newsletter(click here to read it on our website) provides a great picture in that regard.

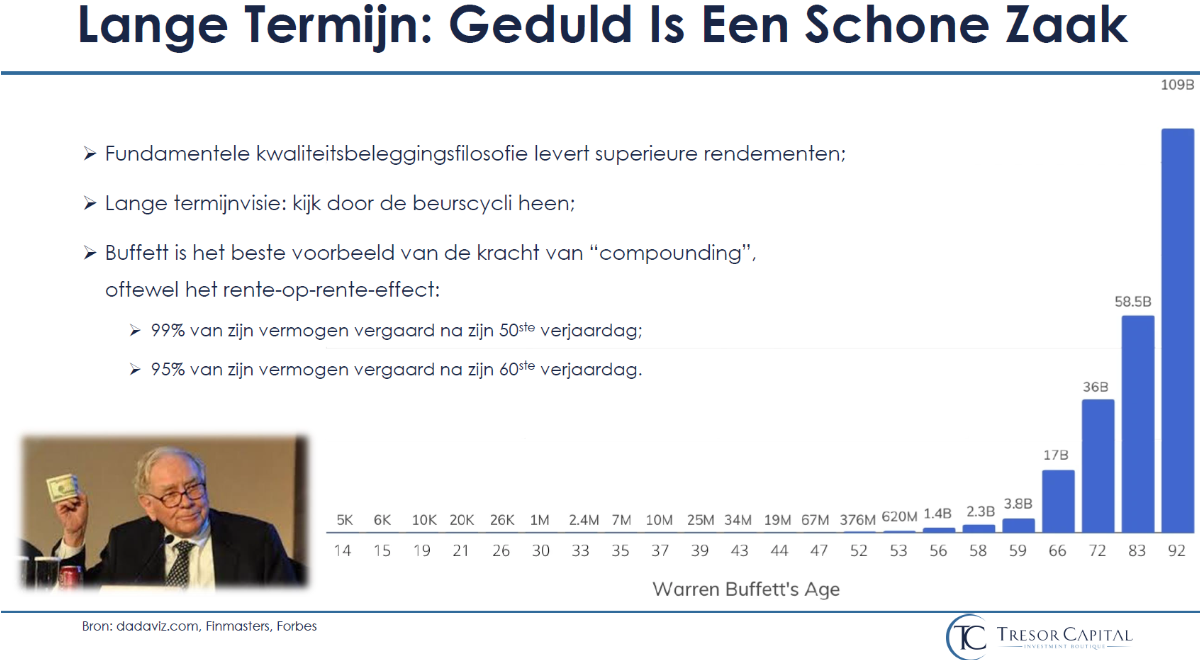

What we want to focus on in closing this monthly report is Buffett’s observation that patience pays off. Above, we shared Buffett’s statement about “rare companies that can invest additional capital at high returns in the future. Owning just one of these companies – and simply holding them – can yield almost immeasurable wealth.”

One discipline that is critical to this is to see through the noise. What do we mean by that? As cited earlier in this article: look past the headlines, look past simplistic ratios such as a P/E ratio and dive deeper into the fundamentals and competitive advantage.

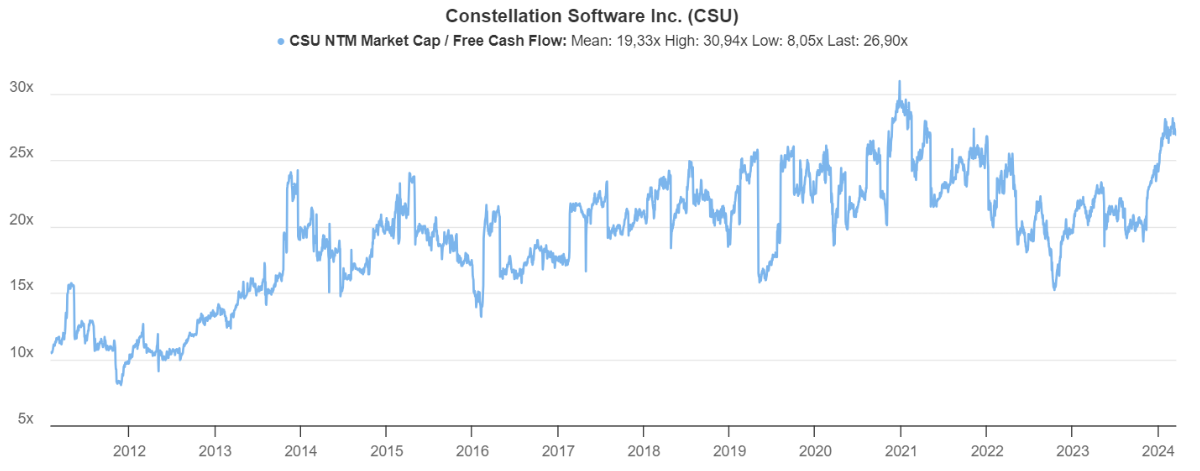

Constellation Software is a fitting real-life example, as this investment holding company of eccentric founder Mark Leonard seems quite pricey based on short-term multiples, as you can see in the image below. The trick to getting really good long-term returns is by sticking with your best holdings, even if the valuation is sometimes seemingly high.

That’s swearing in church with many investors. Buffett’s teacher Ben Graham was the founder of value investing. Simply put, that’s buying a stock for less than it’s worth. As Buffett’s recently deceased business partner Charlie Munger once put it, “Any form of intelligent investing is value investing, where you acquire more than you pay for.”

However, valuation requires more than the simplistic viewing of a P/E ratio. To quote Charlie Munger again, the statement below sums up the gist well:

- “In the long run, it is difficult for a stock to earn a better return than the company that underlies it. If the company earns 6% on invested capital over a 40-year period and you hold it for those 40 years, you won’t achieve much other than a 6% return, even if you originally bought it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a company earns 18% a year on invested capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive-looking price, you get a nice result.”

The return Constellation Software earns on its invested capital has been (well) above 20% for years. For years many investors have argued that Constellation is too expensive in terms of valuation, but meanwhile the stock price keeps running away from them. And if you look back, Constellation has made far more acquisitions and invested far more capital than what these investors were willing to assume in their valuation models at the time.

Mark Leonard once stated:

- “A very special case of value investing is the example of a company that is growing rapidly, which the market expects to stop growing within the next five to seven years, but which in reality continues to grow rapidly for much longer. If you can spot one of these companies, it may seem expensive in terms of its P/E ratio, but may actually be an attractive long-term investment based on the principles of value investing .”

It does deserve a special mention that Mark Leonard has been shouting for years that Constellation is overvalued on the stock market. On the other hand, the Canadian family-owned holding company has long been able to systematically exceed all expectations. So Constellation Software itself is an example of the type of investment Mark Leonard describes above.

Some investors seek a “margin of safety” by buying stocks at a huge undervaluation. At Constellation, we see a margin of safety in the quality of the company, the proven ability of management to continue to perform and thus consistently exceed expectations. Looking back, we can say that the times when the stock seemed “expensive,” in retrospect it was actually quite cheap.

We are by no means arguing that Constellation is a bargain today (although we still see an interesting discount to our calculated intrinsic value), but we are not going to be rushed out of a great company just because it seems fairly valued by today’s standards.

Perhaps finally, it is interesting to note that the founder of value investing, Benjamin Graham, made most of his own money by investing in auto insurer GEICO, now part of Berkshire Hathaway. In fact, GEICO did so well that the price of its shares rose to more than two hundred times the price Graham originally paid.

The share price jump far exceeded the actual earnings growth, and almost from the start the valuation seemed far too high in terms of Graham’s own investment standards. But because he viewed the company as something of a “family business,” he continued to retain a significant portion of the shares despite the spectacular price increase.

Of course, the above does not mean that one should hold onto a stock at all times. In a podcast with Rowan Nijboer, we will soon take a closer look at this article by Akre Capital (from renowned quality and value investor Chuck Akre). Of course, we will keep you informed via newsletters.

PS: we would love to receive your feedback on our newsletters. A positive response is nice, but a critical dissent is also very welcome, we can only improve in the end.

If you have any questions or comments about this e-mail or other matters, please kindly contact us using the details below.

Sincerely,

Michael Gielkens, MBA

Partner