Receive Tresor Capital’s free weekly newsletter, which includes:

- Analyses of family holding companies and serial acquirers

- Deep dives into fundamental investing

- Michel Salden’s keen macro vision

In the world of investing, much attention is paid to balance sheets, income statements and macroeconomic trends. Essential, no doubt. But one of the most critical factors for long-term success is often underemphasized: the quality and drivers of management.

The term “skin in the game,” made famous by Warren Buffett, states that a company’s key people must themselves be significantly invested. As an investor, you entrust your capital to a management team. The crucial question then is: are they acting as a temporary passerby (an agent) or as a dedicated owner (an owner-operator)? The answer to that question has far-reaching implications for your returns.

The ‘Agency’ Problem: The Tyranny of the Quarterly

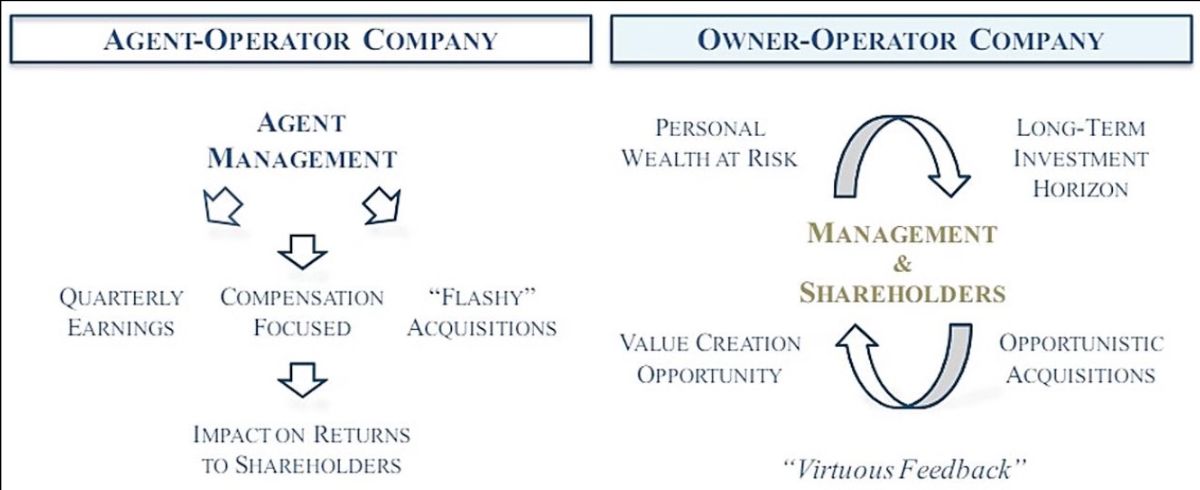

Many publicly traded companies are run by managers whose personal wealth is not significantly connected to the long-term fortunes of the company. Their focus is dictated by the delusion of the day: the next quarterly report. Their interests are not necessarily aligned with those of shareholders, leading to the classic “agency problem.

The pay structure is often the culprit here. When a CEO is rewarded for revenue growth in absolute terms, for example, without looking at the profitability or return on that growth, it can lead to value-destroying acquisitions. Legendary investor Charlie Munger aptly summed this up: “Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.” These perverse incentives can encourage managers to engage in behavior that maximizes their own bonus but is harmful to the shareholder in the long run.

Shockingly, research shows that 78% of managers of publicly traded companies are willing to sacrifice long-term value creation for more stable earnings trends. 80% of managers would even postpone necessary investments in R&D, advertising or maintenance to meet their profit projections. In a survey of CFOs, even 75% said they were willing to sacrifice long-term profits to meet short-term “guidance.

An infamous practical example of this dynamic is General Electric under the leadership of Jack Welch. He was praised for years for invariably exceeding Wall Street’s earnings expectations. However, this was achieved through an obsessive focus on the short term, delaying major investments and artificially polishing the numbers. These policies damaged the company immensely, which explains the dramatic fall in its share price after his departure.

Moreover, this short-term focus is reinforced by the fact that the average period in which investors hold a stock has shrunk from more than seven years in the 1970s to just a few months today.

The Owner-Operator: a virtual circle of value creation

Opposed to this is the “owner-operator”: a manager whose personal wealth is significantly invested in the company. These are often founders or families who have been at the helm for generations. In the investment world, this is called “eat your own cooking”: like a chef eating his own meal, their interests are inherently equal to those of other shareholders.

This dynamic creates a different mindset: thinking in generations rather than quarters. These leaders are investing for the next generation and looking 20 years ahead. This leads to a “virtuous feedback loop.

This long-term vision manifests itself in several strategic choices. Instead of laying off staff during a crisis, such as the corona pandemic, they keep talent on board because they know the company should still be successful three to five years from now. They take a more cautious approach to debt and prefer to finance investments out of their own cash flow, thus avoiding reliance on external financiers in difficult times. Large, risky acquisitions are shunned, in part because their success rate is often between 70% and 90%. Any investment, such as building a new factory, is made only if it creates long-term value and meets a predetermined return requirement.

The proof: the resounding numbers of “Skin in the Game.”

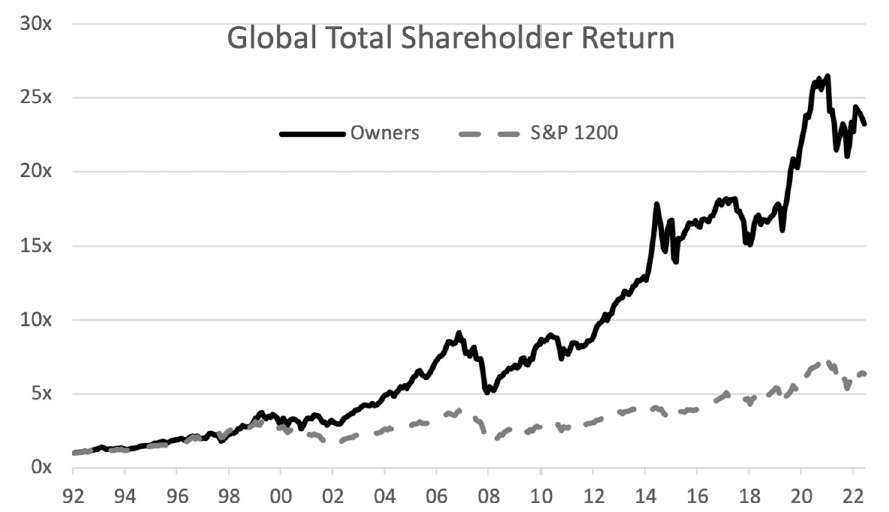

This philosophy is more than an assumption; it is backed by hard data. A recent in-depth study by Steven Wood, entitled “Owners vs. agents: A global examination of the behavior of owner operators“, provides compelling evidence. Wood analyzed nearly 1,300 companies over a 30-year period (1993-2023) and the conclusion is clear: owner-operators achieved a compound annual return of 10.9%, versus 6.3% for the S&P 1200 Global Index.

This significant outperformance stems from a series of consistent behaviors. First, owner-operators achieve significantly higher and more sustainable revenue growth, which is primarily organic. This is due in part to higher customer satisfaction, measurable through tools such as the Net Promoter Score. They also invest more in the company’s future. They grow their workforce faster and invest more in fixed assets. All of this, despite higher operating costs in the short run, leads to a superior return on invested capital (ROIC) in the long run.

Capital management is also different. They pay out less capital through dividends and share repurchases, preferring to reinvest in their own businesses. Finally, they avoid the ‘guidance’ trap: they are much less likely to issue short-term earnings forecasts. This allows them to escape the pressure to “manage” quarterly earnings and focus on building the company for the long term. On a side note, owner-operator stocks can exhibit higher volatility. For the long-term investor, however, this is not a risk, but rather a source of opportunity.

The Tresor Capital approach: a partnership beyond the numbers

For us, selecting the right investments is a search for partners. We focus on holding companies and serial acquirers where families and/or owner-operators are at the helm, because this structure naturally aligns interests.

However, it goes beyond just the ownership structure; it requires an in-depth, qualitative assessment of the people behind the company. We want to talk to the management teams in person to gauge their authenticity and passion. A CEO with a somewhat wild haircut who makes his own coffee because the rest of the team is looking for acquisitions shows a focus on the business. This contrasts sharply with managers who are primarily concerned with their public image. We are alert for “yellow flags,” such as excessive mention of top investors like Warren Buffett, an illogically high turnover in top management, or signs of nepotism.

We have a fondness for family investment holding companies. This structure is often “unconstrained,” meaning that management is free to invest where the best opportunities lie, whether in publicly traded or private companies. A holding company functions almost like an actively managed ETF, a low-cost structure at the holding company level where capital is continually and automatically reinvested in new, value-creating projects.

To reinforce this philosophy, it is only natural for us to have “skin in the game” ourselves. Tresor Capital’s partners invest their private wealth in the same opportunities as for their clients. Thus, our clients’ success also becomes our success as partners, while we also feel the same pain when an investment does not turn out as well.

The conclusion is clear and supported by both academic research and decades of practical experience: ownership matters. In a world increasingly driven by short-term thinking, investing in and alongside owner-operators offers a sustainable path to value creation. It is an investment in a proven model of patience, rational capital management and an unwavering focus on the long term.